Understanding Paradoxes of Voting

Published:

You might have been frustrated by the ways of electing an option democratically, not necessarily because of the outcome of the process, but because of the innate nature of the choice rule employed. In this blog, we will discuss what constitutes an ideal voting rule, and further use a prominent result in social choice theory that asserts the impossibility of such an ideal rule. As a consequence of this result, the nature of voting becomes inherently paradoxical, of which we will understand a few fascinating instances.

On a side note, the contents of this blog are based on a term paper I submitted for the course on Game Theory in the Jan-May 2020 semester at IIT Madras.

The story begins...

The democratic practices involve voting. In a reductionist view, democracy is simply a mechanism to choose an outcome by allowing voting by all the stakeholders. There are N number of voting rules that we can come up with. Interestingly, not all voting mechanisms lead to the same outcome when used by a fixed set of voters trying to elect a candidate from a fixed set of candidates.

Moreover, the voting rules can be manipulated systematically in order to favor a particular outcome. For instance, consider a scenario where stone, paper and scissors are competing for a position. Say the election is to happen in two rounds, where two designated candidates go first and the winner of this round then stands against the remaining third candidate. Here's a twist: there is an election commissioner who has the responsibility to assign candidates to the rounds. Consider if the commissioner decides to put stone and paper against each other in the first round, the outcome of the election would be scissors as the paper wins in the first round but loses to the scissors every time. What would happen if scissors are in the power, and they pick a favourable election commisioner? This leads to a stable democratically-elected authoritarian regime under scissors! Exaggeration aside -- a "democratic" voting applied without understanding loopholes in it can cause serious ramifications. Obviously, one might think: What is an ideal voting rule? Does there exist one? If there is one, why isn't one used everywhere? Let's dive in.

First, we will formalize a few things starting with characterisation of a voter in our discussion. We want our voter to be someone who: (i) has a strict preference between every possible pair of candidates (x, y), and (ii) if she prefers x over y and y over z, then she must prefer x over z. As a consequence, we simply require the voter to provide an order over candidates in a descending preference order. We will call such a voter, a 'rational' voter.

People studied what can be considered an ideal voting rule in mid 20th century as democracy was becoming increasingly popular across the globe. Here is a standard list of characterisitcs majority agree upon: (i) when rational voters vote using a voting rule, the voting rule should collectively produce a rational outcome. That is, like the individual voter, the voting rule should, collectively, output a descending order of preferences over the candidates. What we don't want the voting rule to lead to is a cyclic preference: where candidate x is preferred over candidate y, y over z, but z is preferred over x. With such a cycle, it is impossible to choose one among the many. (ii) Apart from a voter being rational, there should not be any other restrictions put on or privileges given to the voter based on their personal affiliations. (iii) If all voters prefer candidate x over candidate y, then the voting rule's outcome should not prefer y over x collectively. (iv) The final results of voting rule concerning a pair (x, y) should depend only on the voters' preferences pertaining to x and y, and it should not be dependent on voters' tendencies regarding any other candidate z. (v) The voting rule should not allow dictatorship of any single voter, i.e., the outcome should not be dependent on one voter's preferences. To quickly summarize, an ideal voting rule should be rational, should allow every rational voter, should obey voters' consistent preferences, should not influence choice between two candidates based on the presence of third candidate and should not allow dictatorship.

Does there exist a voting rule that satisfies all the characteristics of the ideal voting rule? Answer is NO! Prof. Kenneth Arrow proved this result and he went on to win the Nobel Prize in Economics for his discovery. Once the non-existence is proved, we are inclined to understand what are the drawbacks of different voting rules and if there are loopholes that need to be addressed. The study of different voting rules lead us some very interesting 'paradoxes of voting'.

(1) Condorcet's paradox: One of the earliest paradoxes discovered. Analogous to AC-DC current wars, there was a war for which voting rule was superior in mid 19th century which made people find flaws in each other's voting rules. Condorcet's paradox is a product of the same. Let's call this paradox as 'cycle paradox'. It arises if we have three voters 1, 2, and 3, and three candidates x, y, and z, with following preferences:

| Voter | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferences | x > y > z | y > z > x | z > x > y |

The outcome of majority voting generates a cycle, i.e., x > y > z > x with no clear winner.

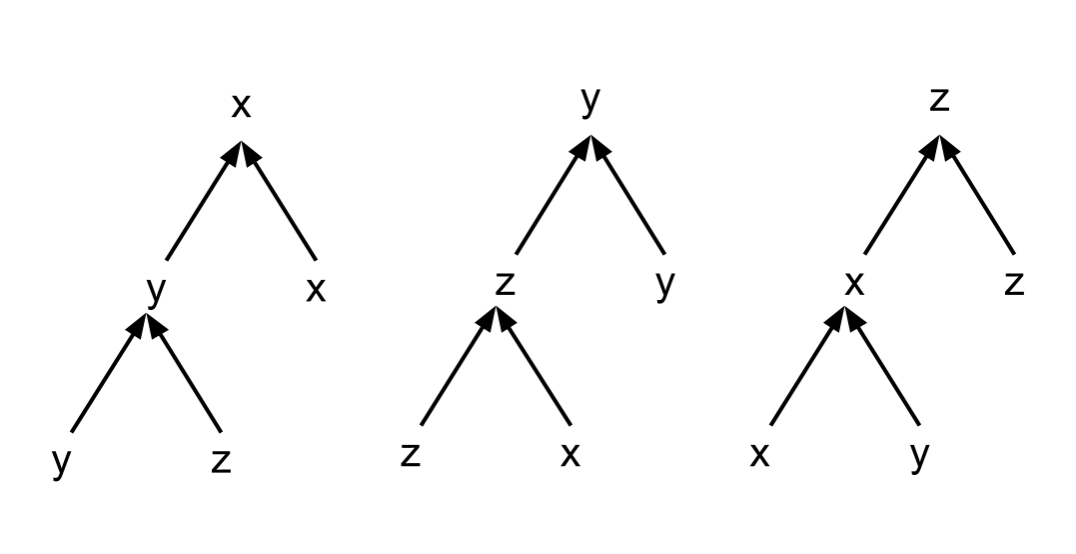

(2) Agenda paradox: This is the same paradox discussed earlier where an election comissioner can orchestrate a democratic autocracy. Let's call this stone-paper-scissors paradox! The paradox arises due to the end result being dependent on the agenda of voting in the two round election.  This image shows three different agenda leading to three different winners. One can possibly do a random assignment of the candidates to the rounds as a solution. However, the assignment itself leads to the result and the democratic process is mere an exercise leading to deterministic outcome conditioned on the assignment.

This image shows three different agenda leading to three different winners. One can possibly do a random assignment of the candidates to the rounds as a solution. However, the assignment itself leads to the result and the democratic process is mere an exercise leading to deterministic outcome conditioned on the assignment.

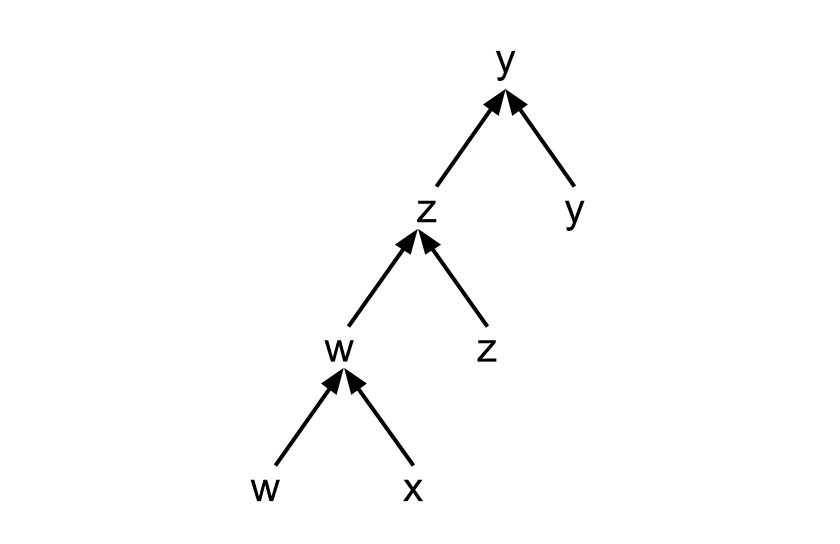

(3) Dominated-winner paradox: This one is my favorite. This paradox arises when you have a preference ordering like this:

| Voter | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferences | x > y > w > z | w > x > y > z | z > w > x > y |

the winner is y, and is consistently dominated by x in every voter's preference, but still goes on to winning the election. Formally, the winner y is called a 'Pareto-dominated winner'. My personal nickname for this paradox is how-come-y-wins-over-x paradox. You must have seen a version of this paradox in real elections too no matter which part of the world you come from.

(4) Majority-winner paradox: This paradox arises in count-based voting rule. Unlike majority rule where a candidate is chosen by sheer number of votes, in count-based rule, each voter gives a rating to the candidates. For instance, 3 for the highest preferred, 2 for the second and 1 for the least preferred. Collectively, we gather total ratings for each candidate and the candidate with highest rating wins. For the the following preference profile,

| Voter | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferences | x > y > z | x > y > z | x > y > z | y > z > x | y > z > x | y > x > z | z > x > y |

The conclusion is...

Democratic voting rules might be flawed inherently, but democracy is the best system we have for governing ourselves. Please feel free to reach out to me if you want to read the original term paper I had submitted as the course requirements. There are many other paradoxes that I could not go through due to lack of time. Hope you had great time reading and learning from this blog.